editorial

Women without land: the persistence of inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean

Claudia Brito, Gender Official, FAO, and Catalina Ivanovic and Viviana Enríquez, FAO consultants

In Latin America, rural women tend to have less access to land and the land they do have is generally of poorer quality.

"Land ownership is a fundamental human right and the existing gender gap in this area is a structural bottleneck of inequality"

58 million women live in the countryside in the region, of whom only 30% possess agricultural land [1]. Many face difficulties in getting title of the land they farm, and in making use of natural resources, including water, to irrigate their fields.

Land ownership is a fundamental human right and the existing gender gap in this area is a structural bottleneck of inequality that States have agreed to tackle with specific measures articulated through the Sustainable Development Agenda 2030.

In particular, indicator 5.a.2 of Development Goal 5 measures: “the proportion of countries where the legal framework (including customary law) guarantees women’s equal rights to land ownership and/or control” [2].

With the aim of supporting countries in their monitoring of this indicator, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has developed and validated an ad hoc methodology, and set up a technical support initiative which by mid-2021 had already achieved results in nine countries: Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Paraguay, Peru, Nicaragua and Uruguay.

The analysis it carried out of the legal and political frameworks in these countries showed that Bolivia, Colombia, Guatemala, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay all have agricultural laws that favor “joint ownership” by requiring that the names of married women and those in de facto partnerships be included in the joint deed document for rural or agricultural land. However, this requirement does not apply to non-rural land, leaving urban and peri-urban women unprotected.

Likewise, the legislation in Guatemala, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay makes provisions in the Civil and Family Codes for the requirement of women’s consent for land transactions only in the case of married couples, whereas Bolivia and Nicaragua also give guarantees for de facto partnerships.

Turning to inheritance, all the countries monitored have laws guaranteeing this right under the same conditions for sons and daughters, and they set aside a proportion of the assets for the spouse. In the case of Bolivia and Peru, both spouses have the same inheritance rights as their descendants, whether there is a will or not. In the countries mentioned, this right is conditioned by the time the couple have lived together, whereas the remaining countries do not recognize de facto partnerships.

It is interesting to note that Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Colombia have earmarked long-term budgets or specific financial resources in their legislative and political frameworks to support women’s access to land and productive services. Nevertheless, their absence in the remaining countries shows the need to legislate and invest in this area.

Under the legal systems of Bolivia, Colombia, Guatemala, Peru and Paraguay, their constitutions recognize customary law and give precedence to the stipulations on gender equality and non-discrimination in cases of conflicts with customary legal systems [3] or the collective ownership of land in ethnic communities. However, none of the countries in the study has regulations that explicitly protect women’s rights of access to land in the legal and political framework at the same time as recognizing the customary ownership of land.

Finally, legislation in both Colombia and Nicaragua sets obligatory quotas for women’s participation in the institutions that are responsible for managing and administering land.

As we see, the region has made significant progress, but also faces many challenges to guarantee women’s rights to land, and action must be taken to change this situation by taking specific measures.

One of these is to adopt standards and policies to make the joint register of all rural and urban goods of married couples and those in de facto partnerships mandatory, with regulations covering those institutions in charge of land registry.

Another would be to develop standards and policies with economic incentives that encourage the joint register of land in both urban and rural areas, such as for example waiving registry fees, or tax rebates on jointly owned property, as well as subsidies for purchasing real estate or properties with joint ownership.

Likewise, it is vital that provisions in Civil and Family Codes that discriminate against equal rights of joint administration and inheritance by spouses and their descendants be revoked or eliminated, both in the case of married couples and those in de facto partnerships or civil unions.

Countries can also create or amend their legislation for the development or financing of Land Funds that promote equal access and include a budget item with a State commitment in the medium and long term.

Finally, it is important to develop strategies for women’s economic empowerment, financial and productive inclusion as an integral part of social protection programs entailing subsidies, loans and preferential rates for the purchase of real estate, property and production insurance and formalizing ownership, among others.

[2] http://www.fao.org/sustainable-development-goals/indicators/5a2/es

[3] Customary legal system: systems that exist at the local or community level that have not been established by the State and whose legitimacy emanates from the values and traditions of indigenous or local groups. Customary legal systems may or may not be recognized in national legislation. https://www.fao.org/3/i8785es/i8785es.pdf

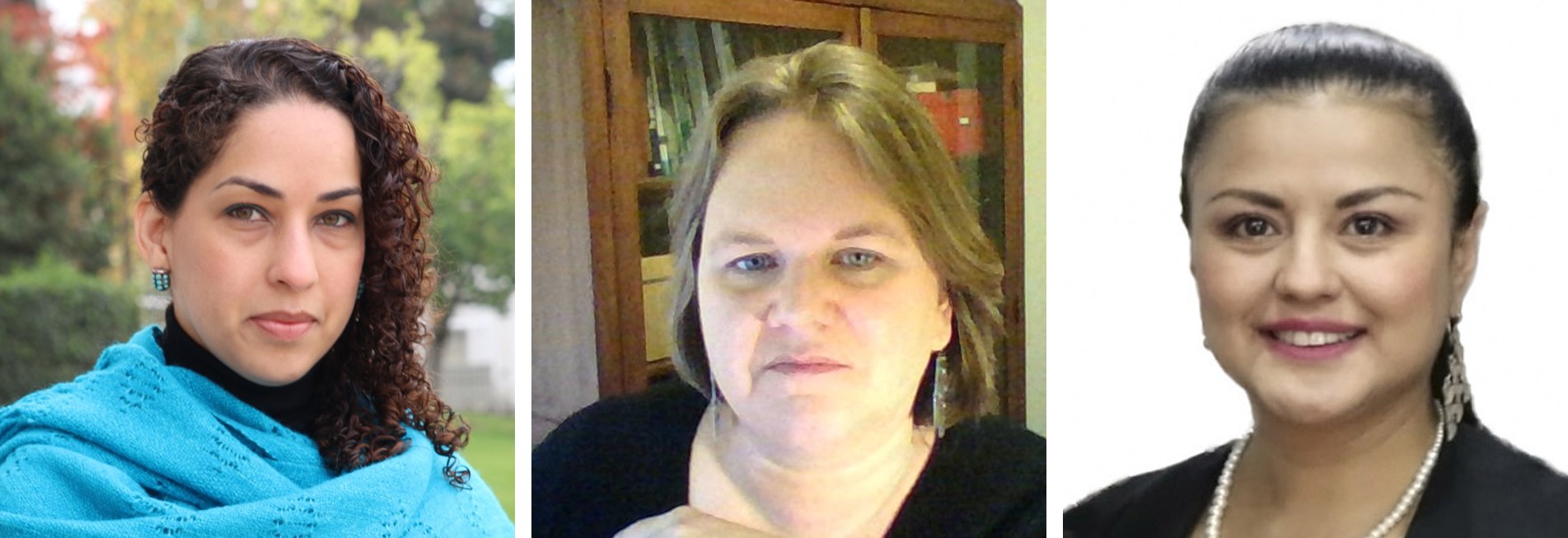

Authors:

Claudia Brito Bruno, Policy, Gender and Social and Institutional System Officer. FAO Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean

Psychologist, with a master's degree in higher education and a doctorate in administration from the University of Montesquieu Bordeaux IV, France. Dr. Brito is a senior strategist for policies, programs and projects in sustainable development, gender equality and advanced human talent development. Her professional experience has given her the opportunity to interact in numerous and diverse environments, with special emphasis on rural areas in more than twenty countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Catalina Ivanovic Willumsen, Gender Mainstreaming Specialist. FAO Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean

Social Anthropologist, Master in Gender Studies from the University of Chile, and PhD in Sociology from the Alberto Hurtado University. Dr. Ivanovic specializes in sociocultural studies of food, and in the development of public policies, programs and projects that address food systems and sustainable development.

Viviana Andrea Enríquez, Regional Monitoring Specialist Indicator 5a2. FAO Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean

Lawyer, specialist in Family Law, Master in Defense of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law before International Organizations, Tribunals and Courts, Colombia. Dr. Enriquez is a jurist with experience in gender approach, public policies, strategic litigation in land restitution and armed conflict. As a regional specialist, she provided technical support to Latin American countries in monitoring indicator 5.a.2.